Eliminate these 6 conversation patterns to improve your relationships

The following six conversation patterns have been identified by communication experts Yvonne Agazarian and Anita Simon as the most important to recognize and change in order to communicate more effectively and authentically. Most relationships end due to a communication breakdown and thus learning these has the potential to dramatically improve your relationships success.

The following six conversation patterns have been identified by communication experts Yvonne Agazarian and Anita Simon as the most important to recognize and change in order to communicate more effectively and authentically. Most relationships end due to a communication breakdown and thus learning these has the potential to dramatically improve your relationships success.

The best way to learn this system is to take an introductory SAVI (System for Analyzing Verbal Interaction) course so you can practice hands-on in a structured environment. The next best thing is to buy the adjacent book read it and do the exercises in the book as well as the free ones online on the Conversation Transformation website.

The following is mostly directly copied or paraphrased straight out of the book and will give you a general idea of what it’s about.

The primary purpose of this post is to act as a quick summary cheat sheet to help simplify the awareness process so behavior changes can be done more easily. Much of the context and explanations are missing and can only be gleaned from purchasing the book, which I highly recommend doing. Hopefully the following will arouses some of your curiosity.

The 6 basic patterns are:

- Yes-Buts

- Mind-Reads

- Negative Predictions

- Leading Questions

- Complaints

- Verbal Attacks

To test your own conversation savviness take the free online pre-test here.

1. Yes-Buts

Yes-Buts are the hallmark of what are called “polite fights” and the most reliable way to get into an argument. People tend to try and use them in a an attempt to be diplomatic or making unpleasant news easier to hear. The problem with them is three fold:

- They send two conflicting messages at the same time which makes it difficult for the brain to process. As a result..

- People only hear the “but”. It’s human nature to notice difference so the “yes” part is usually lost.

- Artificial difference can be created and then become a source for further conflict.

Stealth “Yes” & “But”

[ezcol_1half]

- I understand where you’re coming from…

- I see your point…

- That may be true…

- I know that seems like the obvious solution…

- You could say that…

- While that’s one way to look at things…

- You’re absolutely right…

- Sure….

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end]

- …however…

- ….nevertheless….

- …..on the other hand….

- ….still….

- ….only then….

- ….have you considered….

- ….it’s just that….

- ….and yet….

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Solution:

- Do three sincere specific builds on the other persons’s idea

- Then phrase your concern as a broad open-ended question

This strategy shifts the frame of the conversation to build and explore rather than creating sugar-coated opposition.

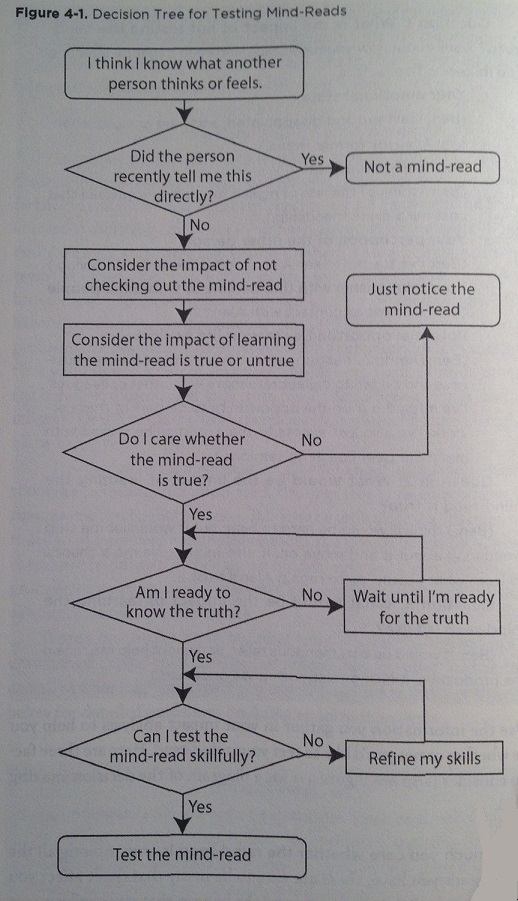

2. Mind-Reads

Mind reads are one of three sources of primal anxiety in the SCT model. The important thing here is to distinguish between a projection and a perception. Mind-reads often occur when trying to read body-language so fact checking becomes extremely important. Another important concept here is also known as “reality-testing”.

Examples of mind-reads

[ezcol_1half]

- “Marilyn’s tired,”

- “Jim is still upset,”

- “You’re in a good mood today”

- “I can tell my boss is disappointed in me”

- “Adam clearly prefers working with Tom”

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

- “Our neighbors have a happy marriage”

- “I know Jack wants a raise”

- “You didn’t enjoy that party”

- “They’re waiting for us to make the first move”

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Mind-reads are assumptions about what other people are thinking or feeling regarded as facts. Mind-reads feed on ambiguity. The following are the most common factors that create mind-reads.

- Silence

- Vagueness

- Body language

- Absence of Voice tone

[ezcol_1half]

Biases that influence mind-reads

- Personal tendencies

- Worries and fears

- Hopes and wishes

- Stereotypes & generalizations

- Hearsay & rumors

- Past experiences with people

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

Why mind-reads persist

- Lack of awareness

- Fear of the answers

- Lack of trust

- Group norms.

- Active discouragement

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Solution:

- State the thought you’re having.

- Ask a yes-or-no question

3. Negative Predictions

Negative predictions act like black holes, places where our time and energy go to die. Negative are also one of three sources of primal anxiety in the SCT model. When we make negative predictions, we treat our worries and fears about the future as if they’re facts.They are often thus self-fulfilling. Why do we sometimes expect the worst?

“The future is inherently uncertain, and living with uncertainty can feel uncomfortable, even unbearable. Predictions give us a sense of control by creating the illusion that we know what will happen.”

The three primary factors that drive negative predictions are, attempts to manage emotions, reliance in fixed ideas, and generalizations from past experiences. Positive predictions while not as common can also be just as detrimental. Negative predictions have a lot in common with mind-reads as both involve constructing an imagined reality by treating our speculations as facts. Unlike mind-reads where an unknown assumption can be tested, here the future is inherently unknowable.

Solution:

Questions to Undo Negative Predictions

[ezcol_1half]

Questions for Gathering Facts:

- Can I know whats going to happen in the future?

- Am I aware that l’m treating my prediction about the future as though it were already true?

- Have I had any positive experiences in past similar situations?

- When I’ve had negative experiences in similar situations, what factors contributed to those outcomes?

- What is different about my situation now, compared to similar past situations that ended badly?

- What factors in my current situation might impact the outcome l’m worried about?

- Which of those facts can I influence or control?

- What resources and options do have?

- What relevant facts am I missing, and how can I gather those facts?

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

Questions for Planning:

- Knowing what has happened int he past, what could I do differently this time?

- What steps can I take to help prevent the outcome I fear and make a better outcome more likely?

- Are there any contingency plans I want to put in place?

Question for Managing Uncertainty:

- If l’m finding it difficult to sit with uncertainty, what can i do right now to help myself?

[/ezcol_1half_end]

4. Leading Questions

Often the most important information we can receive is something we don’t want to hear: a disagreement with our ideas, challenge to our perspective, or objection to our plans. If you find you frequently don’t get that kind of information you may be using leading questions.

In general there are four types of Questions:

- Broad Questions: Open-ended questions that invite others’ thoughts, conclusions, opinions, or proposals.

- Narrow Questions: Direct, specific questions asking for facts or for yes/no or either/or answers.

- Leading Questions: Opinions in question form, implicitly seeking agreement rather than new information–or, in some cases, seeking no answer at all.

- Righteous questions: Attacks in question form, expressing blame, indignation, or outrage.

Leading questions have two components embedded within them:

- An opinion

- A question

The opinion makes it clear what the “right” response to the question is.

Examples:

[ezcol_1half]

- Most negative contractions: aren’t, don’t, isn’t, can’t, won’t, wouldn’t

- “Aren’t these fruitcakes delicious?”

- “Don’t you agree?”

- “Don’t you think?”

- “Isn’t that right?”

- “Ya know?”

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

- “Wouldn’t you agree?”

- “Yes?” or “Right?”

- Using the words: really, truly, honestly

- “Is that really/truly/honestly what you want?”

- “Do you really/truly/honestly believe that?”

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Being asked a leading question puts you in a bind. If you give the “right” answer, you may feel like you’ve been coerced or manipulated, even if that answer is truthful. People who use leading questions are often seen as being pushy, closed-minded, or domineering. This type of pressure tends to provoke one of two opposing reactions: defiance or compliance. They discourage innovation and imagination and mask conflicts rather than resolving them. If used by a leader it can quickly create an “information vacuum” where no one dares defy the boss. Most people who use leading questions have no idea they’re doing it. Advertisements are chalk full of them.

Solution:

Separate the opinion and the question into two separate statements.

5. Complaints

A sense of hopelessness is the defining feature of this most common unproductive of communication. The main message is that some aspect of our life is unfair, too much, or not enough, and there’s nothing we can do about it. The accompanying voice tone is whining or frustrated. When we complain, we’re taking a passive role, talking as though we’re helpless victims of our circumstances.

The practical problem of complaining is that it acts as a substitute for taking productive action. Expressing our displeasure’s outward in what’s wrong with the situation rather than inward on what we might do to make things better. Complaints tend to elicit one of three unhelpful responses:

- Joining

- Arguing

- Trying to help

For many people a natural response to complaining is a yes-but contradiction. When a person is complaining, proposals from somebody else usually aren’t helpful at all. By suggesting that something will help, you’re telling the person that they’re wrong which often will just lead to arguing.

Complaints are deceptive, diverting our attention from the true sources of trouble. The secret to understanding complaints is the following underlying issues.

- The person wants something

- They feel powerless to get it

Solution:

For self:

- What do I want?

- What proposal can I make to help get that to happen?

For other:

- What do you want?

- What proposal can you make to help get that to happen?

This strategy helps shift the mindset from that of a victim to that of a problem solver. The goal is to replace feelings of dissatisfaction or resentment with a focus on a clear goal, and making proposals replaces passivity and helplessness with active effort. In regards to other complaining, it’s a shift in a person’s own mindset, not the introduction of new, better ideas from the outside, that makes it possible for them to stop complaining and start taking action. The goal here is to empower others to solve their own problems.

Sometimes people are not interested in problem solving and merely want to vent. If this is the case ask them what kind of response the’d like from you. Such as:

- “What would be most useful for you right now?”

- “Would you like me to help you talk through this situation to try to find a way to improve it, or is it better for me to just listen and hear what you’re going through?”

6. Verbal Attacks

Verbal attacks are often used when we experience anger, frustration, irritation, annoyance or other similar feelings.

[ezcol_1half]

Instead of expressing those feelings in a straight forward way such as:

- “I’m angry,”

- “I’m irritated,”

- “I’m annoyed,”

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

We vent them indirectly, targeting other people with a hostile voice tone:

- “She has no right to treat me like this,”

- “Now you’ve gone and ruined everything,”

- “It’s all your fault!”

- “You ruined it!”

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Forms of Verbal attacks:

[ezcol_1half]

- Accusations & blame

- Accusatory mind-reads

- Labeling, name-calling, put-downs, and profanity

- Threats & retaliatory remarks

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

- Sarcastic jabs

- Expressions of outrage & indignation

- Righteous questions

- Neutral words with a hostile tone or inflection

[/ezcol_1half_end]

The toxic power of attacks stems primarily from how misleading they are. Just because someone uses the words “I feel”, doesn’t mean they’re expressing a feeling. For example:

[ezcol_1half]

- “I feel you’re being selfish.”

- “I feel as though you’re smothering me,”

- “I feel like you never appreciate how much I do for you.”

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

- “I feel you’re treating the staff unfairly”

- “I feel like you’re not committed to this imitative.”

[/ezcol_1half_end]

What’s being “honestly” expressed aren’t feelings but attacks. A feeling is an emotional experience, like anger, fear, or happiness. Direct statements of feeling like “I’m angry” are not attacks and usually not perceived as attacks by other people.

Watch out for blameful interpretations that are feeling look-a-likes such as: abandoned, betrayed, rejected, ignored, criticized, put down, cheated, used or violated. Examples: “You abandoned me” or “You betrayed me”.

Emotions do get communicated through attacks but not in a direct, clear way. They leak out through the blame in our words, the edge in our voice tone, or both. The feeling underneath “You’re being selfish” might be disappointment or anger. The feeling underneath “I feel betrayed” might be anguish or sorrow. Some attacks merge a feeling statement together with an accusation-for instance,”You made me really angry.” There’s a feeling in there (“angry”), but the main message coming through is blame (“you made me” feel this way).

In addition to misleading the people who use them, attacks also mislead other people who hear them, including whoever is getting attacked. What drives us to attack is something happening internally: a strong feeling like anger or frustration. But the way were talking focuses all the attention on something external: a situation that’s upsetting us, a person who did something we didn’t like, or anyone or anything else were targeting with our hostility. Our own rnisdirected focus, away from our feelings and onto something else, will tend to mislead those around us.

Ineffective Responses to Attacks

Focusing on the Situation: Avoiding it or Trying to fix it

- Dismissing the other person’s concern (“Don’t worry abut it.” “It’s no big deal.”)

- Making proposals (Why don’t you…” “Have you tried…?”)

Focusing on the People: Laying Blame or Diverting Blame

- Counterattacks (“You’re so negative!” “You make such a big deal out of everything.”)

- Self attack (“It’s all my fault.” “I always do the wrong thing.” “I’m a bad mother/friend/manager/etc.”)

- Self Defense (“It’s not my fault,” “I was only trying to help.” “I did the best I could”)

Goals that focus on punishing the other person or trying to make them change (ex. getting then to feel guilty or admit they were wrong) are unlikely to lead to a good outcome.

When someone is yelling or raising their voice, staying calm and quiet is more likely to infuriate then than to help them settle down. Responding to an attack with self defense can be even more provocative. Attacking and defending go hand in hand, with each one tending to invite the other. Whenever people get stuck in an attack-self defend communication pattern, the defender holds as much responsibility for the breakdown as the attacker and has at least as much power to repair the breach.

The primary information expressed in any verbal attack is about the person who’s delivering it.

Solution:

- Recognize. Identify your feelings, state them clearly, and rate their intensity on a scale of 1 to 5. (Coach Listen, with empathy. If necessary, point out feeling look-alikes and gently probe for the true underlying emotional states.)

- Strateglze. Identify a goal for what you want to have happen with the person you feel like attacking, Alternatively, make a plan for helping yourself feel better that does not involve the other person. (Coach: Check to be sure that the goal is productive, and if you think the person could do better, encourage them to come up with an even more productive goal)

- Verbalize (if appropriate). Practice clearly stating the feelings, facts, proposals, or questions you would like to communicate to the other person. Continue practicing until your certain your message is free of hostility, blame, outrage, and other negative overtones. Then identify a good place and time to talk, and work toward achieving your goal. (Coach: Check to be sure that the way the person is communicating is not likely to cause additional problems. For example, Point out any hostility or blame that is still leaking out. After the conversation, provide consultation on how the discussion went.)

List of Feelings that may underlie attacks

[ezcol_1third]

agitated

alarmed

angry

anguished

annoyed

anxious

apprehensive

ashamed

bitter

bored

confused

cranky

dejected

desperate

disappointed

discouraged

dismayed

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third]

distressed

embarrassed

enraged

envious

exasperated

fearful

frightened

frustrated

furious

grouchy

grumpy

guilty

helpless

hopeless

humiliated

hurt

irritated

[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_1third_end]

jealous

lonely

nervous

overwhelmed

pained

powerless

resentful

sad

scared

shocked

tense

terrified

uncomfortable

uneasy

worried

[/ezcol_1third_end]

Guidelines for Effective Mirroring

- Match the other person’s voice tone but with slightly less emotional intensity

- Use either the same words they used or different words that

capture the same underlying message - Don’t add in any new ideas

- Continue until the hostility diminishes

Only by reflecting another person’s feeling can you show that you’ve really understood what is important to them.

[ezcol_1half]

What they’re expressing:

- High Feeling

- Medium Feeling

- Low Feeling

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

How you respond:

- Resonate (mirror the emotions & ideas)

- Reflect (paraphrase their ideas)

- Resolve (engage in problem solving)

[/ezcol_1half_end]

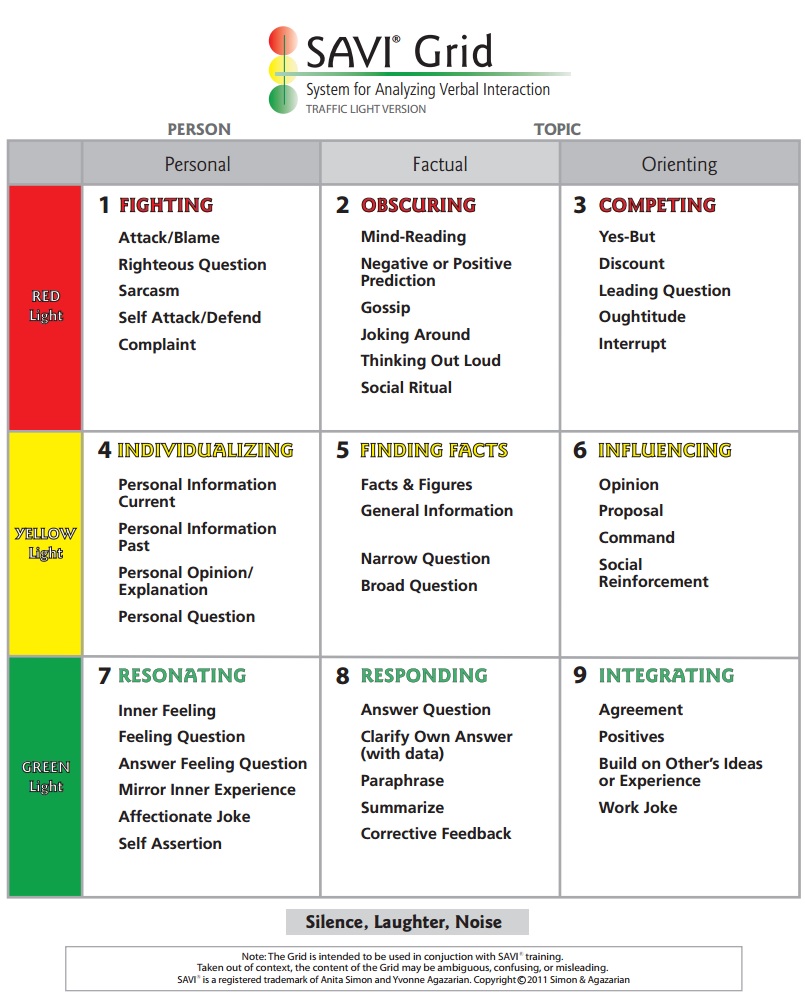

SAVI (System for analyzing verbal interaction)

The above 6 patterns are merely part of a larger comprehensive strategy used to analyze verbal interactions.

There are 3 basic entropic things in communication that lead to “noise” and reduce the chance of information properly going through.

- If you say “yes, but” you are a closed system.

- If you are being ambiguous you are avoiding information content.

- If you are redundant you are avoiding the feeling emotion of what you are saying.

The following grid categorizes all content of conversations. You can use it as a guide to figure out where you are in an interaction with someone. It gives you ideas of what square you may want to move in if you are finding there is a breakdown in communication.

“In addition to using green-light behaviors yourself, you can invite others to move into green light by asking a question. Any direct answer to a question is a green-light behavior, giving proof that information is flowing and making it easier for that flow to continue. Its no accident that questions play a large role in many communication strategies, including the ones we’ve discussed in this book. In yes-but conversations, broad questions can help promote creative thinking and problem solving. In conversations dominated by mind-reads or negative predictions, questions can help replace assumptions with data. And when someone is complaining, asking the right types of questions can help them shift from helpless passivity to constructive action. Just keep in mind that for any question to be effective, it needs to get answered. Its the potential to shift a conversation into green light-by soliciting an answer to create a two-way exchange of information that makes questions so powerful.”

Online quizzes to help you fine tune your skills:

You-tube video lectures:

- Application of SAVI (7 parts)